Download PDF

Andrew Jayasuria

4th year medical student

University of Auckland

Associate Professor Andy Wearn

MBChB, MMedSc

Head of the Medical Programme Directorate

Associate Professor at the Clinical Skills Centre

The University of Auckland

Associate Professor Anna Vnuk

MBBS, EdD

Associate Professor in Medicine at Flinders University

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar

MBCHB, MMedSc

Director of the Clinical Skills Centre

The University of Auckland

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges regarding the teaching and learning of the male genital examination as part of the undergraduate medical curriculum relates to the extent of practice opportunities with patients in the clinical setting.

OBJECTIVES

To quantify how many male genital examinations have been performed on real patients by medical students at the point of graduation, and to explore the context of performing the examination with patients.

METHODS

A self-completed, online, anonymous questionnaire was developed and deployed as part of a two-centre study. Data were collected from final-year medical students in the period just after graduation from the medical programmes at the Universities of Auckland and Flinders in late 2013.

RESULTS

The combined response rate was 42.9% (134/312). The median for the number of male genital examinations performed was 2-3. A total of 16% of medical students had never performed a male genital examination. Self-reported opportunities for performing the male genital examination were strongly related to the setting (e.g. urology and paediatrics/neonates). The largest self-reported barrier was related to patients being uncomfortable being examined by female students.

CONCLUSIONS

For some students, their only experience of performing male genital examinations is on a model in simulation. Opportunities to perform the male genital examinations that students feel comfortable with are rare. The delivery of medical curricula needs to address this issue.

Introduction

The teaching and learning of the male genital examination as part of the medical curriculum is complex. Traditional methods of teaching sensitive examination include textbooks, models, videos, small groups, and lectures (1). Genital teaching associates (GTA) have also been used increasingly in undergraduate medical programmes (2). In New Zealand, use of GTAs in a simulated clinical environment has been found to be effective in increasing medical student's skills and confidence (3). However, there are numerous advantages to using real patients as part of teaching and learning (1). The most valued method identified by medical students is with patients (1,4,5). This is shown by their increased confidence in their ability to differentiate the abnormal from the normal, as well as the ability to make this distinction accurately when given the opportunity to learn from real patients (1,,4,5).

One of the challenges is the extent to which medical students have the opportunity to practise with real patients in the clinical setting. Factors preventing opportunities to perform the male genital examination are multifactorial. Difficulties include conflict between ethical and educational needs (6), student anxiety (4), student gender (5,7,8), and patient preferences (7,8). In one study, obstruction by clinical staff was the least identified reason as a barrier for performing the male genital examination (7), unlike for other sensitive examinations such as the female pelvic examination (9).

Opportunities for medical students to perform sensitive examinations with a patient can be rare (9,10). With regards to the male genital exam, the lack of opportunity is highlighted in an international survey of 104 medical schools. The study showed that a male genital examination would typically never be performed by their medical students at the time of their graduation, in approximately 50% of surveyed medical schools (11). In a context with cultural differences to Australasia, a study conducted at the King Saud University College of Medicine identified that 34.6% of interns had never completed a male genital examination at the point of their graduation (8). In another study from two Saudi Arabian medical programmes, the majority of students (75.2%) had never performed a male genital examination (7). There is a paucity of information in the literature on the rates of performance of the male genital examination in the Australasian context.

This study aims to quantify the number of male external genital examinations on real patients at the point of graduation, as well as barriers to performing this examination on real patients at two Australasian medical schools. Self-reported competence of the examination and differentiating between abnormal and normal is also explored.

Methods

SETTING AND SUBJECTS

Medical students from Flinders University and The University of Auckland in their final year were eligible to complete an anonymous online survey at the point of their graduation in late 2013.

For both medical programmes, the male genital exam is not formally taught in the simulated or preclinical setting. Opportunities for performing these examinations on real patients as an appropriate part of patient assessment occur in different years for the different medical schools. Flinders University has a four-year Doctor of Medicine (MD) programme, of which opportunities to perform male genital examinations on real patients occur in the clinical years (Years Three to Four). The Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) programme at the University of Auckland starts in year two, and is a six-year curriculum with opportunities to perform the male genital examination during Years Four to Six.

SURVEY DESIGN

The survey was created with a United Kingdom based team (12), and then adapted for New Zealand and Australia (13-14), taking in to account different ethnic categories. The survey tool was electronic and anonymous.

In the questionnaire, students were asked to estimate, using an ordinal categorical range scale (none, 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6-9, 10-19, 20-49, 50-99, 100+), the number of male genital examinations they have performed throughout their medical school training. The students were also asked to comment separately on their ability to differentiate between normal and abnormal, as well as their perceived competence in performing these examinations. Free text responses for each examination was available. Basic demographic data (i.e. ethnicity, gender, age) were also collected in the survey.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee and the Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee at Flinders University.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive and comparative statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data with the IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 computerised statistical package.

Thematic analysis was used to identify, analyse, and report patterns within the qualitative data (free text comments) (15). HB read, coded and themed the whole data set. AJ, AW, and AV independently reviewed the data against the themes and revised the analysis. A consensus was reached by all four authors. Barriers and opportunities to practise the male genital examination identified, reviewed, and defined certain themes. For each theme, illustrative quotations were selected.

Results

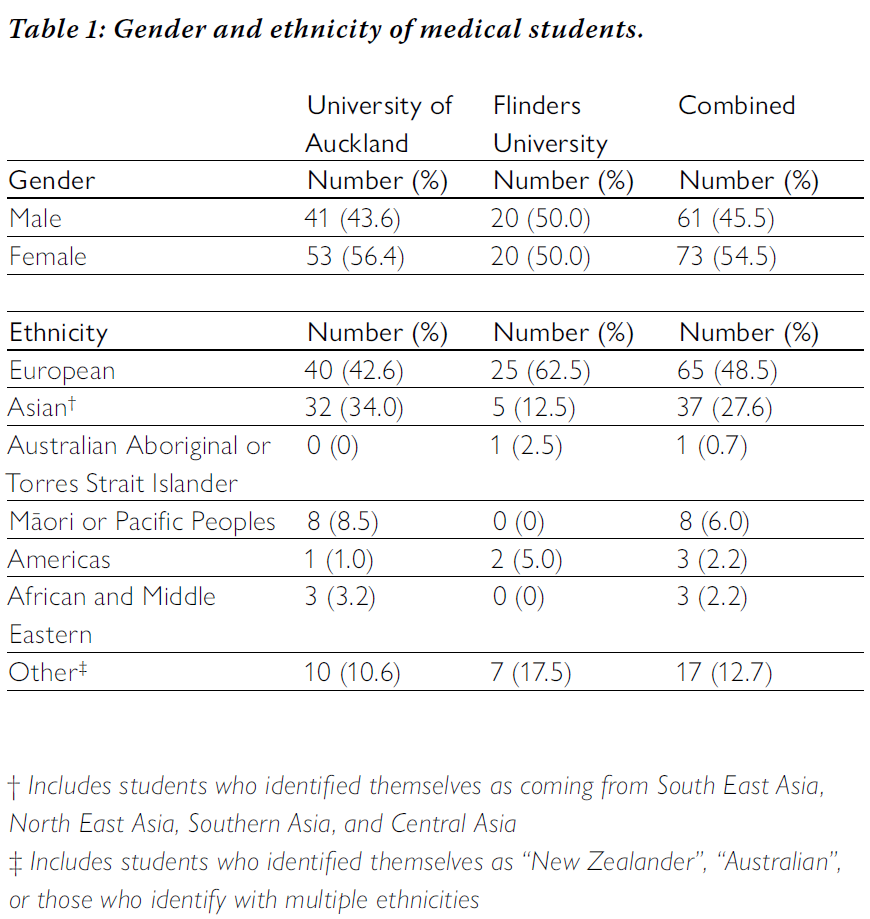

The survey's overall response rate was 42.9% (134/312). At Flinders University, the response rate for the survey was 32.8% (40/122), while at the University of Auckland the response rate for the survey was 49.5% (94/190). For the combined data set, the median age of the students was 25 years (interquartile range (IQR), 4 (24-28) years). The University of Auckland's students' median age of 24 years (IQR, 3.3 (23-26.3) years) was significantly lower (Mann-Whitney U-test, P < 0.05) than the Flinders University students' median age of 27 years (IQR, 6.3 (26-32.3) years).

Table 1 shows the demographic details of the study population.

Andrew Jayasuria

4th year medical student

University of Auckland

Associate Professor Andy Wearn

MBChB, MMedSc

Head of the Medical Programme Directorate

Associate Professor at the Clinical Skills Centre

The University of Auckland

Associate Professor Anna Vnuk

MBBS, EdD

Associate Professor in Medicine at Flinders University

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar

MBCHB, MMedSc

Director of the Clinical Skills Centre

The University of Auckland

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges regarding the teaching and learning of the male genital examination as part of the undergraduate medical curriculum relates to the extent of practice opportunities with patients in the clinical setting.

OBJECTIVES

To quantify how many male genital examinations have been performed on real patients by medical students at the point of graduation, and to explore the context of performing the examination with patients.

METHODS

A self-completed, online, anonymous questionnaire was developed and deployed as part of a two-centre study. Data were collected from final-year medical students in the period just after graduation from the medical programmes at the Universities of Auckland and Flinders in late 2013.

RESULTS

The combined response rate was 42.9% (134/312). The median for the number of male genital examinations performed was 2-3. A total of 16% of medical students had never performed a male genital examination. Self-reported opportunities for performing the male genital examination were strongly related to the setting (e.g. urology and paediatrics/neonates). The largest self-reported barrier was related to patients being uncomfortable being examined by female students.

CONCLUSIONS

For some students, their only experience of performing male genital examinations is on a model in simulation. Opportunities to perform the male genital examinations that students feel comfortable with are rare. The delivery of medical curricula needs to address this issue.

Introduction

The teaching and learning of the male genital examination as part of the medical curriculum is complex. Traditional methods of teaching sensitive examination include textbooks, models, videos, small groups, and lectures (1). Genital teaching associates (GTA) have also been used increasingly in undergraduate medical programmes (2). In New Zealand, use of GTAs in a simulated clinical environment has been found to be effective in increasing medical student's skills and confidence (3). However, there are numerous advantages to using real patients as part of teaching and learning (1). The most valued method identified by medical students is with patients (1,4,5). This is shown by their increased confidence in their ability to differentiate the abnormal from the normal, as well as the ability to make this distinction accurately when given the opportunity to learn from real patients (1,,4,5).

One of the challenges is the extent to which medical students have the opportunity to practise with real patients in the clinical setting. Factors preventing opportunities to perform the male genital examination are multifactorial. Difficulties include conflict between ethical and educational needs (6), student anxiety (4), student gender (5,7,8), and patient preferences (7,8). In one study, obstruction by clinical staff was the least identified reason as a barrier for performing the male genital examination (7), unlike for other sensitive examinations such as the female pelvic examination (9).

Opportunities for medical students to perform sensitive examinations with a patient can be rare (9,10). With regards to the male genital exam, the lack of opportunity is highlighted in an international survey of 104 medical schools. The study showed that a male genital examination would typically never be performed by their medical students at the time of their graduation, in approximately 50% of surveyed medical schools (11). In a context with cultural differences to Australasia, a study conducted at the King Saud University College of Medicine identified that 34.6% of interns had never completed a male genital examination at the point of their graduation (8). In another study from two Saudi Arabian medical programmes, the majority of students (75.2%) had never performed a male genital examination (7). There is a paucity of information in the literature on the rates of performance of the male genital examination in the Australasian context.

This study aims to quantify the number of male external genital examinations on real patients at the point of graduation, as well as barriers to performing this examination on real patients at two Australasian medical schools. Self-reported competence of the examination and differentiating between abnormal and normal is also explored.

Methods

SETTING AND SUBJECTS

Medical students from Flinders University and The University of Auckland in their final year were eligible to complete an anonymous online survey at the point of their graduation in late 2013.

For both medical programmes, the male genital exam is not formally taught in the simulated or preclinical setting. Opportunities for performing these examinations on real patients as an appropriate part of patient assessment occur in different years for the different medical schools. Flinders University has a four-year Doctor of Medicine (MD) programme, of which opportunities to perform male genital examinations on real patients occur in the clinical years (Years Three to Four). The Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) programme at the University of Auckland starts in year two, and is a six-year curriculum with opportunities to perform the male genital examination during Years Four to Six.

SURVEY DESIGN

The survey was created with a United Kingdom based team (12), and then adapted for New Zealand and Australia (13-14), taking in to account different ethnic categories. The survey tool was electronic and anonymous.

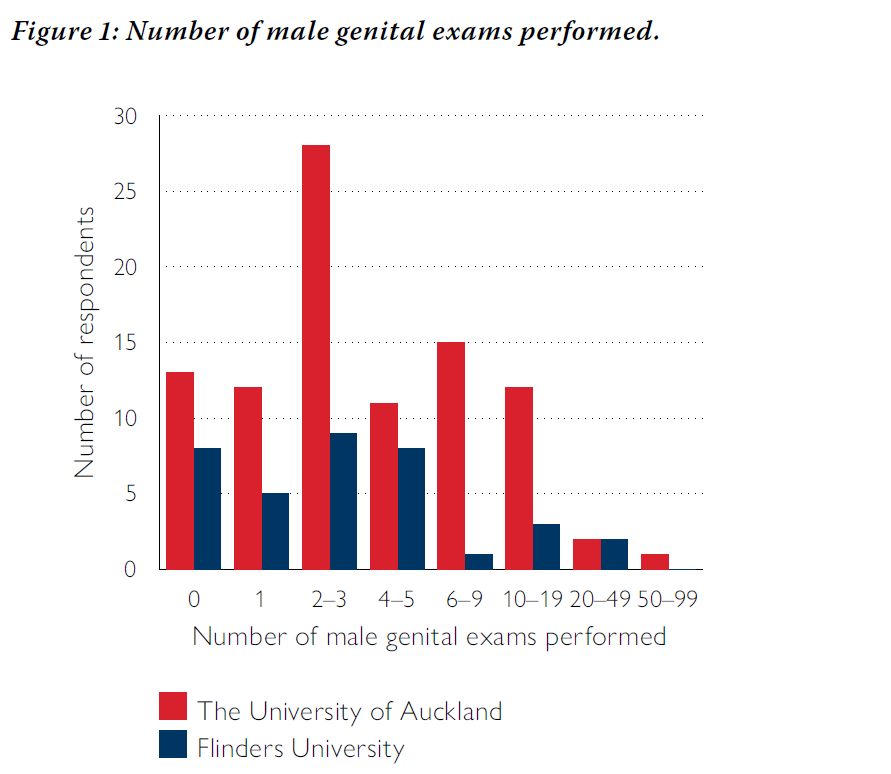

In the questionnaire, students were asked to estimate, using an ordinal categorical range scale (none, 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6-9, 10-19, 20-49, 50-99, 100+), the number of male genital examinations they have performed throughout their medical school training. The students were also asked to comment separately on their ability to differentiate between normal and abnormal, as well as their perceived competence in performing these examinations. Free text responses for each examination was available. Basic demographic data (i.e. ethnicity, gender, age) were also collected in the survey.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee and the Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee at Flinders University.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive and comparative statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data with the IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 computerised statistical package.

Thematic analysis was used to identify, analyse, and report patterns within the qualitative data (free text comments) (15). HB read, coded and themed the whole data set. AJ, AW, and AV independently reviewed the data against the themes and revised the analysis. A consensus was reached by all four authors. Barriers and opportunities to practise the male genital examination identified, reviewed, and defined certain themes. For each theme, illustrative quotations were selected.

Results

The survey's overall response rate was 42.9% (134/312). At Flinders University, the response rate for the survey was 32.8% (40/122), while at the University of Auckland the response rate for the survey was 49.5% (94/190). For the combined data set, the median age of the students was 25 years (interquartile range (IQR), 4 (24-28) years). The University of Auckland's students' median age of 24 years (IQR, 3.3 (23-26.3) years) was significantly lower (Mann-Whitney U-test, P < 0.05) than the Flinders University students' median age of 27 years (IQR, 6.3 (26-32.3) years).

Table 1 shows the demographic details of the study population.

The median number of male genital examinations performed was 2-3. The number of male genital exams performed in each location is seen in Figure 1.

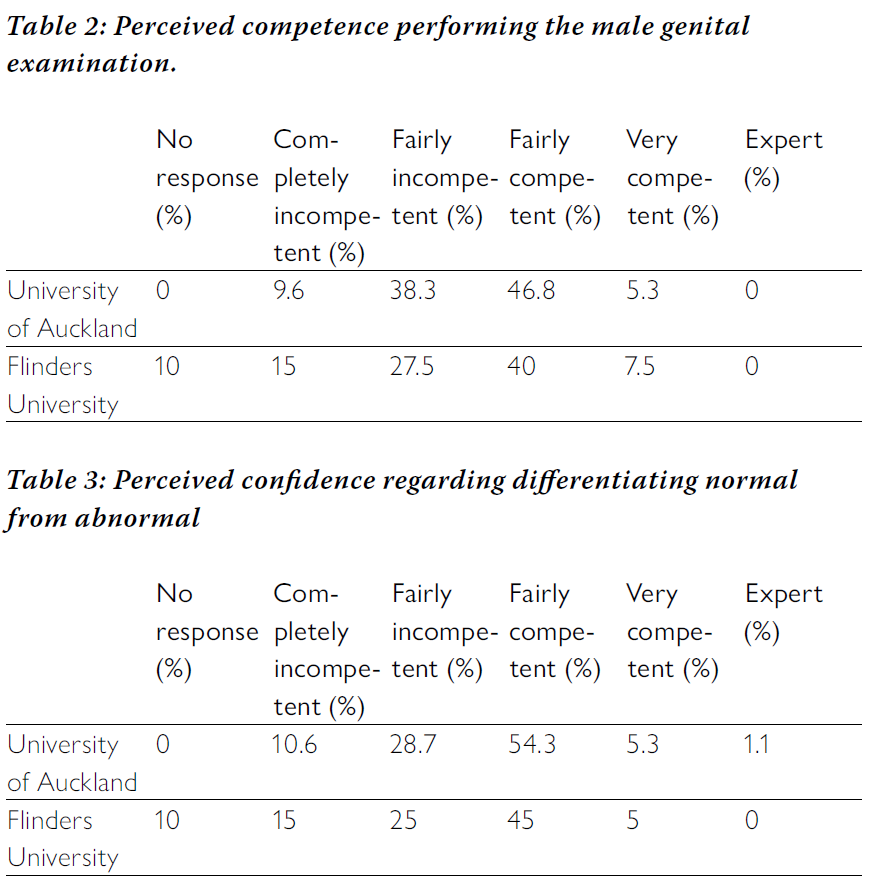

A total of 47.9% and 42.5% of students felt incompetent performing the male genital examination at The University of Auckland and Flinders University, respectively. With regards to differentiating normal from abnormal, 39.3% of students at The University of Auckland and 40.0% of students at Flinders University felt incompetent.

Table 2 shows the perceived competence in performing the male genital examination, and Table 3 shows the perceived confidence in differentiating normal from abnormal findings.

Table 2 shows the perceived competence in performing the male genital examination, and Table 3 shows the perceived confidence in differentiating normal from abnormal findings.

There was a moderate, and statistically significant, correlation between the number of male genital exams performed and perceived competence regarding the exam (Spearman's rho, 0.625). There was a moderate, and statistically significant, correlation between the number of exams performed and perceived confidence in distinguishing between normal and abnormal for the male genital examination (Spearman's rho, 0.627).

Qualitative analysis of free text comments provided four main themes. Firstly, that students identified certain clinical attachments as providing a better opportunity to perform the male genital examination. Secondly, the gender of the student was seen as a barrier to perform the examination, with patients being more uncomfortable being examined by female students. Thirdly, students wanted more teaching. Fourthly, students felt incompetent performing the examination.

“Only exposure in urology and paediatrics...and E.D." (Female; age 33 years; the University of Auckland; response identity (ID) 87)

“All in paediatric population" (Female; age 24 years; Flinders University; response ID 5)

“Usually males [patients] were understandably shy to have me in the room for genitalia exams. If I was, I mainly observed." (Female; age 24 years; the University of Auckland; response ID 57)

“Would have liked more teaching about examination of testicular lumps/masses." (Female; age 271 years; Flinders University; response ID 6)

“Bit unsure of what to do other than inspect." (Female; age 23 years; the University of Auckland; response ID 52)

Discussion

We found that rates of performance of the male genital examination by medical students were low, but higher than the available international literature, taking into account cultural differences between Saudi Arabia and Australasia (4-7). In a study based in Saudi Arabia 75.2% of students, by the end of graduation, had never performed male external genital examination on real patients as compared with 16.2% of final-year medical students in this study (7). Our study found that the median number of male genital examinations performed was 2-3. This was higher than a similar study done in Saudi Arabia: median number 1-2 (8).

Quantitative analysis did not identify any statistically significant predictors of lower or higher rates of attainment for the male genital examination. The significant difference in age of student at the two locations is unsurprising, since the majority of students enter through an undergraduate pathway for the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) at The University of Auckland, whereas entry to medical school at Flinders University is almost exclusively through a graduate entry pathway.

However, our qualitative analysis showed that opportunities to perform the male genital examination appeared to be related to the clinical rotation that the student was attached to. Students reported that surgical-based rotations in hospital (particularly urology) and paediatric rotations seemed to be better in terms of opportunities to perform the male genital examination. With regards to barriers to perform the male genital examination on real patients, students identified gender (female gender of student) as a reason for reduced opportunities to perform the male genital examination. This was similar to the findings of other studies (4,7,8). Other issues raised by students related to the amount of teaching they would have liked to receive and their perceived competence performing the examination.

The moderate and statistically significant correlation between the number of exams performed and perceived confidence in distinguishing between normal and abnormal found in our study was also supported by the literature (5,8). However, this is not a strong correlation and our quantitative analysis indicates that some students feel incompetent with regards to performing the male genital examination and differentiating normal from abnormal, despite performing examination on patients.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our data was retrospective and is based on the memory of medical students over multiple years during their degree. Second, our data was self-reported and the relationship between perceived and actual competence cannot be verified. Third, the response rate was low; however, this was better than is typical of online surveys (16). Fourth, the data are five and a half years old and the curriculum may have improved. Fifth, we did not perform an analysis to determine if our respondents were representative of all students (by age/ethnicity). Finally, as the data were collected from two Australasian institutions (New Zealand/Australia), it may not be possible to extrapolate more widely.

Despite the limitations, our results raise important questions regarding teaching the male genital examination to medical students. Firstly, is it necessary to teach the male genital examination to undergraduate students? Unlike other sensitive examinations such as the rectal examination and the pelvic examination, the male genital examination is not specified by accrediting bodies in Australia (17) and New Zealand as a skill that pre-vocational junior doctors are expected to be able to perform. Secondly, if medical students are expected to be able to perform the male genital examination, how many male genital examinations should students be expected to perform? Finally, given that the requirement for this examination is rare, is the teaching and learning of the male genital examination sustainable? Further qualitative data from educators, clinicians, and students is required in order to answer these questions.

To our knowledge, this is the first paper that quantifies the number of male genital examinations performed by medical students in the Australasian context and investigates the confidence and competence in performing male genital examinations by medical students.

In conclusion, some final-year medical students have never performed the male genital examination in a clinical setting during the extent of their degree. Opportunities (e.g. facilitated by surgical and paediatric rotations) and barriers (e.g. related to gender and lack of formal teaching) were identified by students. If this examination is to be considered necessary for students to learn prior to graduation, the teaching and learning of the male genital examination in the undergraduate medical programme should take these factors into account and ensure that students have adequate learning experiences and opportunities to become competent.

References

About the authors

Andrew Jayasuria is a fourth year medical student at The University of Auckland, who completed a 2018 summer studentship under the supervision of Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar.

Associate Professor Andy Wearn, MBChB, MMedSc, is the Head of the Medical Programme Directorate and Associate Professor at the Clinical Skills Centre, The University of Auckland.

Associate Professor Anna Vnuk, MBBS, EdD, is an Associate Professor in Medicine at Flinders University.

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar, MBCHB, MMedSc, is the Director of the Clinical Skills Centre at The University of Auckland.

Acknowledgements

Professor Jim Parle for collaborating on this project.

Funding

Summer studentship funding at The University of Auckland (2018-2019)

Correspondence

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar

Email: [email protected]

Postal Address: University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019,

Auckland 1142, NEW ZEALAND

Work telephone number: +64 9 923 8862

Qualitative analysis of free text comments provided four main themes. Firstly, that students identified certain clinical attachments as providing a better opportunity to perform the male genital examination. Secondly, the gender of the student was seen as a barrier to perform the examination, with patients being more uncomfortable being examined by female students. Thirdly, students wanted more teaching. Fourthly, students felt incompetent performing the examination.

- CLINICAL ATTACHMENTS

“Only exposure in urology and paediatrics...and E.D." (Female; age 33 years; the University of Auckland; response identity (ID) 87)

“All in paediatric population" (Female; age 24 years; Flinders University; response ID 5)

- GENDER OF STUDENT

“Usually males [patients] were understandably shy to have me in the room for genitalia exams. If I was, I mainly observed." (Female; age 24 years; the University of Auckland; response ID 57)

- REQUEST FOR MORE TEACHING

“Would have liked more teaching about examination of testicular lumps/masses." (Female; age 271 years; Flinders University; response ID 6)

- PERCEIVED LACK OF COMPETENCE

“Bit unsure of what to do other than inspect." (Female; age 23 years; the University of Auckland; response ID 52)

Discussion

We found that rates of performance of the male genital examination by medical students were low, but higher than the available international literature, taking into account cultural differences between Saudi Arabia and Australasia (4-7). In a study based in Saudi Arabia 75.2% of students, by the end of graduation, had never performed male external genital examination on real patients as compared with 16.2% of final-year medical students in this study (7). Our study found that the median number of male genital examinations performed was 2-3. This was higher than a similar study done in Saudi Arabia: median number 1-2 (8).

Quantitative analysis did not identify any statistically significant predictors of lower or higher rates of attainment for the male genital examination. The significant difference in age of student at the two locations is unsurprising, since the majority of students enter through an undergraduate pathway for the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) at The University of Auckland, whereas entry to medical school at Flinders University is almost exclusively through a graduate entry pathway.

However, our qualitative analysis showed that opportunities to perform the male genital examination appeared to be related to the clinical rotation that the student was attached to. Students reported that surgical-based rotations in hospital (particularly urology) and paediatric rotations seemed to be better in terms of opportunities to perform the male genital examination. With regards to barriers to perform the male genital examination on real patients, students identified gender (female gender of student) as a reason for reduced opportunities to perform the male genital examination. This was similar to the findings of other studies (4,7,8). Other issues raised by students related to the amount of teaching they would have liked to receive and their perceived competence performing the examination.

The moderate and statistically significant correlation between the number of exams performed and perceived confidence in distinguishing between normal and abnormal found in our study was also supported by the literature (5,8). However, this is not a strong correlation and our quantitative analysis indicates that some students feel incompetent with regards to performing the male genital examination and differentiating normal from abnormal, despite performing examination on patients.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our data was retrospective and is based on the memory of medical students over multiple years during their degree. Second, our data was self-reported and the relationship between perceived and actual competence cannot be verified. Third, the response rate was low; however, this was better than is typical of online surveys (16). Fourth, the data are five and a half years old and the curriculum may have improved. Fifth, we did not perform an analysis to determine if our respondents were representative of all students (by age/ethnicity). Finally, as the data were collected from two Australasian institutions (New Zealand/Australia), it may not be possible to extrapolate more widely.

Despite the limitations, our results raise important questions regarding teaching the male genital examination to medical students. Firstly, is it necessary to teach the male genital examination to undergraduate students? Unlike other sensitive examinations such as the rectal examination and the pelvic examination, the male genital examination is not specified by accrediting bodies in Australia (17) and New Zealand as a skill that pre-vocational junior doctors are expected to be able to perform. Secondly, if medical students are expected to be able to perform the male genital examination, how many male genital examinations should students be expected to perform? Finally, given that the requirement for this examination is rare, is the teaching and learning of the male genital examination sustainable? Further qualitative data from educators, clinicians, and students is required in order to answer these questions.

To our knowledge, this is the first paper that quantifies the number of male genital examinations performed by medical students in the Australasian context and investigates the confidence and competence in performing male genital examinations by medical students.

In conclusion, some final-year medical students have never performed the male genital examination in a clinical setting during the extent of their degree. Opportunities (e.g. facilitated by surgical and paediatric rotations) and barriers (e.g. related to gender and lack of formal teaching) were identified by students. If this examination is to be considered necessary for students to learn prior to graduation, the teaching and learning of the male genital examination in the undergraduate medical programme should take these factors into account and ensure that students have adequate learning experiences and opportunities to become competent.

References

- Jha V, Setna Z, Al-Hity A, Quinton ND, Roberts TE. Patient involvement in teaching and assessing intimate examination skills: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):347-57.

- McAlpine K, Steele S. Missing the mark: current practices in teaching the male urogenital examination to Canadian undergraduate medical students. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10(7- 8):281-5.

- McBain L, Pullon S, Garrett S, Hoare K. Genital examination training: assessing the effectiveness of an integrated female and male teaching programme. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):299.

- Dabson AM, Magin PJ, Heading G, Pond D. Medical students' experiences learning intimate physical examination skills: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:39.

- Powell HS, Bridge J, Eskesen S, Estrada F, Laya M. Medical students' self-reported experiences performing pelvic, breast, and male genital examinations and the influence of student gender and physician supervision. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):286-9.

- Coldicott Y, Pope C, Roberts C. The ethics of intimate examinations - teaching tomorrow's doctors. BMJ. 2003;326(7380):97-101.

- Abdulghani HM, Haque S, Irshad M, Al-Zahrani N, Al-Bedaie E, Al-Fahad L, et al. Students' perception and experience of intimate area examination and sexual history taking during undergraduate clinical skills training: a study from two Saudi medical colleges. Medicine. 2016;95(30):e4400.

- Alnassar SA, Almuhaya RA, Al-Shaikh GK, Alsaadi MM, Azer SA, Isnani AC. Experience and attitude of interns to pelvic and sensitive area examinations during their undergraduate medical course. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(5):551-6.

- Bhoopatkar H, Wearn A, Vnuk A. Medical students' experience of performing female pelvic examinations: opportunities and barriers. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(5):514-9.

- Bhoopatkar H, Weam A, Vnuk A. Audit and exploration of graduating medical students' opportunities to perform digital rectal examinations as part of their learning. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:617-8.

- Hunter SA, McLachlan A, Ikeda T, Harrison MJ, Galletly DC. Teaching of the sensitive examinations: an international survey. Open J Prev Med. 2014;4(1):41-9.

- Parle J, Watts A. Intimate examinations: UK students don't do them any more.Barcelona, Spain: Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE); 2016 Aug 27-31.

- Statistics New Zealand. Ethnicity New Zealand standard classification, version V1.0. 2005.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian standard classification of cultural and ethnic groups (ASCCEG). 2nd ed (revision 1). 2011.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77- 101.

- Duncan N. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ. 2008;33:301-14.

- Graham IS, Gleason AJ, Keogh GW, Paltridge D, Rogers IR, Walton M, et al. Australian curriculum framework for junior doctors. Med J Aust. 2007;186(7 Suppl):S14-9.

About the authors

Andrew Jayasuria is a fourth year medical student at The University of Auckland, who completed a 2018 summer studentship under the supervision of Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar.

Associate Professor Andy Wearn, MBChB, MMedSc, is the Head of the Medical Programme Directorate and Associate Professor at the Clinical Skills Centre, The University of Auckland.

Associate Professor Anna Vnuk, MBBS, EdD, is an Associate Professor in Medicine at Flinders University.

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar, MBCHB, MMedSc, is the Director of the Clinical Skills Centre at The University of Auckland.

Acknowledgements

Professor Jim Parle for collaborating on this project.

Funding

Summer studentship funding at The University of Auckland (2018-2019)

Correspondence

Dr Harsh Bhoopatkar

Email: [email protected]

Postal Address: University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019,

Auckland 1142, NEW ZEALAND

Work telephone number: +64 9 923 8862